Trying to Resolve the "Two Kinds of Art"

What's supposed to happen to all of the commercial artists?

Hi,

Last week, I wrote about the stock images I love. Now that has me thinking about the stock images we have today, and the stock images of the future.

The big difference between stock images of the past and the future is the fundamental change in the way they’re created. Until recently, there really wasn’t any way to avoid involving a human in the creation of images - photos, illustration or otherwise - and that necessarily means some creativity is going to slip in.

The funny thing is that, to create things you kind of need to be… creative. And while I believe creativity is inherently human and something we all possess, it’s undeniable that many industries have grown around the concept of selling your creativity to others so they don't need to create anything (in other words, so they don't need to be creative).

Deciding to lean into creativity as a career is seemingly indulgent to some. They imagine a life of toiling in the finer things: writing poetry and having interesting thoughts about concepts and themes, and later that day feeling bad about some feelings you're having. If someone says they’re “an artist” when asked what they do for a living, I don’t doubt that many people picture a painter toiling away in a messy studio, a tortured writer sitting in an empty room with a typewriter, or an avant-garde performance artist laying on the floor of an art gallery doing something inscrutable - probably with food or garbage.

But the professional artists I knew growing up with a commercial illustrator as a father were a different breed. They were career artists from the coal mines of creativity. Skilled trades-people who put their personal voice and message to the side to lend their ability to companies and commercials. It was an exchange of goods - creativity in exchange for survival.

The legacy of many antiquated mediums of art making have their roots in that kind of labour: printmaking, engraving, map-making, sign-painting, pottery and the many trades grown around doing things with wood. Over time, these two streams of creative genealogy - the poets and the tradespeople - have overlapped and the poets in art schools now learn to letter-press their prose on pieces of precious parchment, while the tradespeople's jobs become automated and they're left doing it "for the artistry" of the craft. Yet the distinction between "fine" and "commercial" art remains in our collective minds.

As we find more and more ways to offload the trade labour of creative people to machines, it reveals that the artists who honed their craft in the service of companies were themselves always seen by the company more as machines (or the engines driving machines) than as people. My dad tells me about the ad agencies who bragged about burning through artists with impossible deadlines and unlivable wages, ultimately signaling his exit from that line of work for more stable employ. Now he teaches young artists what's coming for them and the cycle seems to continue. I can't help but be a bit grateful that the industry has become so unsustainable that I don't need to feel bad for not wanting to join in on that grind - not more than I already have, at least. Maybe eventually the cycle will end when no one can get paid to be creative at all.

When the machines can make pictures, the companies say that's better for them.

Suddenly we’re asking ourselves: if machines create pictures, are they creative too? I would argue machines produce images, making them productive, not creative.

“Even better!” The companies say. “We actually value productivity!”

We're All Artists (Even You)

Hidden in the legacy of commercial art is the creativity of people. That’s what I was so drawn to in the stock images of the 1800s - there’s a craft, a voice, and a humanity to that work that we can’t help but feel. We can see a bit of ourselves reflected in it, even if it's just as simple as noticing our shared humanity with someone from the past. If cheap, multi-purpose images stop being created by people and instead are just produced by machines, then what are we going to feel about them in one hundred and fifty years? Will anybody even care?

As the machines take the jobs of the people who labour in creativity, I feel the boundary between "fine" and "commercial" art falter. If there's a distinction between these streams, maybe it's just art that is made for art's sake, versus art that's made to survive. If storyboards and advertising don't pay the bills anymore, then we're just doing it for it's own sake, right? Did the machines make it fine art by producing some themselves?

The issue with this idea is that I don't really even agree with the dichotomy to begin with - the two streams, the binary of "fine" and "commercial" art. It’s all a fallacy.

I challenge the notion that commercial art isn't fine and that fine art isn't commercial. The more ways we have to divide who we are and what we do, the more tools we give powerful people to gouge into those divisions and pry them apart into chasms. Now more than ever we need allies in the battle for our relevance to the system - comrades in the war for our humanity.

That's why I say we're all artists. We need to be. When we can stay clumped together in the wonderfully vague category of "artist," we can support each other and draw on each other for energy and inspiration. I can't see why I wouldn't want to be lumped in with someone writing music for video games, drawing plans for a building or making anything else that they're moved to. That ability to create makes us who we are. It makes us creative instead of productive. It makes us human.

If we're all artists, we're all artists. We share something in us that makes us want to use that label, at the very least. When I look back a century or more at the work made by craftspeople building a table, painting a sign or drawing a picture - regardless of what it's for - I see a lineage of creativity that I can trace in time back to myself. I see a record of someone existing and having the ability to create. I don't see the same thing happening from images produced by machines. I can't imagine, two hundred years from now, looking at a picture generated by a computer in 2023 and caring about it much at all.

The label "artist" is one I wear with pride - even if it doesn't really explain exactly what I do. It covers the big-picture. I make things. I create.

And this is my favourite part: so do you.

Have a beautiful day!

Love,

Simon 💀🫀🧠

The images throughout this post use the typeface Avara by Raphaël Bastide, with the contribution of Wei Huang, Lucas Le Bihan, Walid Bouchouchi, Jérémy Landes. Distributed by velvetyne.fr.

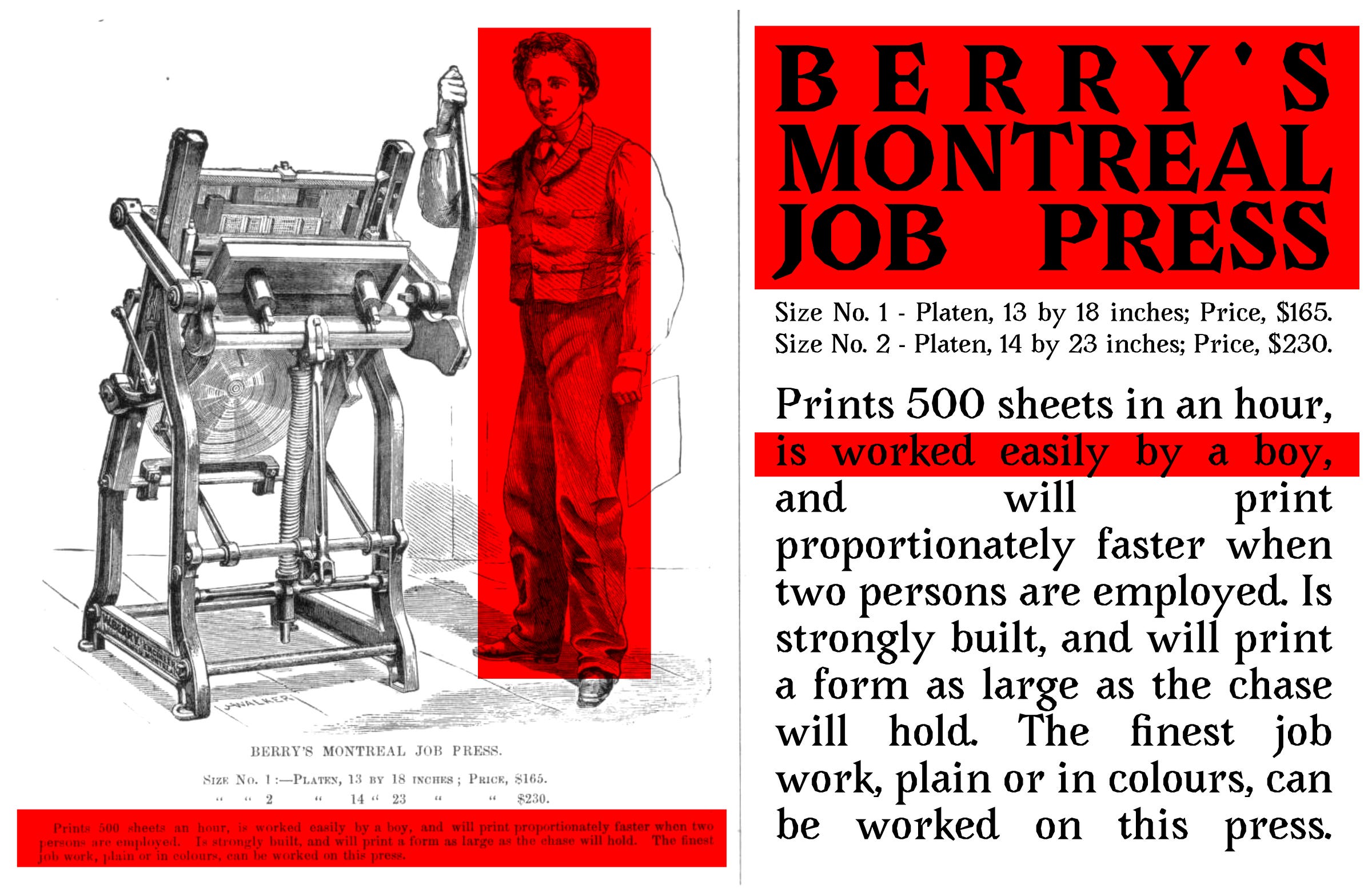

The illustrations and engravings are all from this type specimen book from the Montreal Type Foundry, printed in 1865.

🔗 Links & Thinks 🧠

I've been reading a lot of books recently, which has been a nice change of pace from the unending barrage of podcasts and YouTube videos I typically subject myself to.

If you've read The Name of the Wind or any other Patrick Rothfuss books, I highly recommend the little spin off The Narrow Road Between Desires which came out last year. It's full of some of my favourite writing in any fiction and is a lovely little story, too.

If you hate books but like feeling smart by listening to people much smarter than you (my favourite thing) I recommend listening to the podcast This Machine Kills. This recent episode was a real eye-opener to me and asks an amazingly important question: Does the World Feel $800 Billon Better?

🔔 Simon Status Update:

What I'm Making Right Now

I mentioned last week that I've realized something about what I needed to finish my video on the COMPUBOT project. Since then, I've been dabbling at writing a script for it and finding that challenging and entertaining in how unused to that kind of work I am. It's going to be interesting, if nothing else!

I've also been plugging away at a revision to the look or "brand" for Robot Fan Club - more to come soon!